The Khayelitsha Commission was the outcome of over a decade of struggles on safety and justice. Led by the SJC, social movements based in Khayelitsha, such as the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC), Equal Education (EE) and Free Gender, supported by Ndifuna Ukwazi (NU) and Triangle Project (TP), campaigned for the Western Cape government to establish the Commission. Campaigns relating to individual cases of police inefficiency experienced by TAC, SJC, EE and Free Gender members and their families were drawn together into a united campaign.

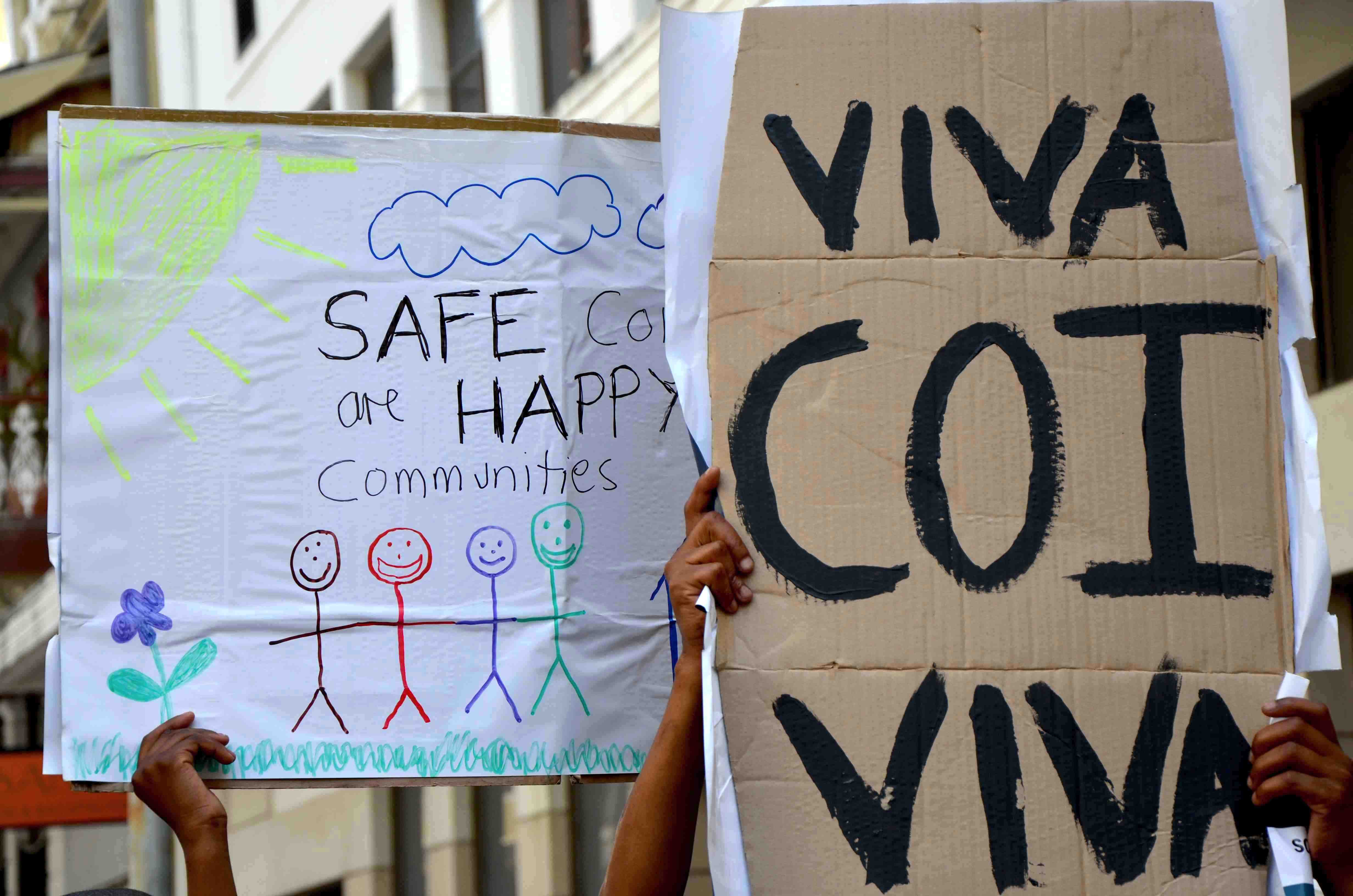

Khayelitsha is one of South Africa’s largest townships and home to the majority of Cape Town’s informal settlement residents. Everyday in Khayelitsha people are robbed, raped and murdered. Crime, violence, and a lack of safety are part of daily life. Basic necessities that many people take for granted such as using a toilet or walking in a well-lit street can be life-threatening, especially for people living in informal settlements.

When we first advocated for a commission of inquiry in 2011 the Minister of Police opposed it. Once it was established, the Minister went to the High Court and the Constitutional Court to try stop it or reduce its powers. He failed to do this. That judgment allowed the Commission to go ahead and set the first prec edent on the powers and duties of the police, the right of communities to hold police accountable and the duty and right of a province to protect its resi- dents from violent crime.

The Commission itself was a truly ground-breaking moment. For the first time in South Africa many of the inner workings of the police were made public as tens of thousands of pages of SAPS information was made available. It offered the opportunity for residents to tell their stories and senior officers had to account to the public. The Commission identified twenty clear recommendations, which have the potential to change the face of policing and justice in South Africa, particularly in poor and working class communities.

One of the most damning findings of the O’Regan-Pikoli Commission of Inquiry into policing in Khayelitsha was that “a system of human resource allocation that appears to be systematically biased against poor black communities” had survived twenty years into post-apartheid democracy. The Commission concluded that, “the survival of this system is evidence of a failure of governance and oversight in every sphere of government.”

The SJC’s Safety and Justice Programme is campaigning to ensure that these recommendations are implemented, while building democratic power for just and equitable policing in poor and working class areas through organising and education.

There has been good progress made at the local level with a commitment to implementing the recommendations from SAPS leadership. We continue to engage with, and campaign for, all stakeholders, including the Provincial Government, to implement recommendations where applicable.

On a national level, the Minister’s refusal to take action left us with no alternative but to take him to court. In March 2016 the SJC and EE launched an application in terms of the Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act 4 of 2000 against the Minister of Police and acting National Commissioner. The court application is to compel them to urgently review and change the inequitable and irrational allocation of police resources in poor and working class areas and to ultimately give substance to the Commission’s recommendations. The SJC is represented by the Legal Resource Centre.

Given the profile of the case, the Nyanga Community Police Forum (Nyanga CPF) approached us to join as Applicants. The Nyanga police precinct has had the highest number of murders in the country for the last six consecutive years but is the fourth least resourced police precinct in the Western Cape. The police challenged this intervention. A court order on 23 September 2016 found in our favour, and affirmed the right of all CPFs to ensure that the police service is transparent and held accountable to the communities they serve. Now the case will continue with the CPF as an applicant.